Advancing SDG 3 using AI: Reducing Maternal Mortality Rates in the U.S.

Executive Summary

- In the U.S., there are 17 maternal deaths for every 100,000 live births.

- The U.S. has a maternal mortality ratio (MMR) over double that of comparable countries.

- Artificial Intelligence-based tools offer an opportunity to drastically reduce the number of maternal deaths.

- Reducing maternal deaths works towards advancing the UN SDG target (3.1.) of reducing global MMR to less than 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030.

UN SDG 3

The United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are an urgent call for action by all developing and developed countries to address 17 key issues – from poverty, climate action and gender inequality through to health and wellbeing. SDG 3 is centred upon ensuring healthy lives and promoting wellbeing for all at all ages.

Amongst 9 different targets, the UN has set out the need to reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births (Target 3.1). That is, it looks to reduce the number deaths due to complications from pregnancy or childbirth (UNICEF, n.d.)[1]. This specifically targets SDG 3: Good Health and Wellbeing (ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages).

The Problem: Maternal Mortality

Maternal deaths – mortality due to complications from pregnancy or childbirth – are a substantial public health concern in the United States (U.S.). Causes of death vary widely, with cardiomyopathy and other cardiovascular conditions, haemorrhage, and other chronic medical conditions all constituting important factors. All of these can have a catastrophic impact on families.

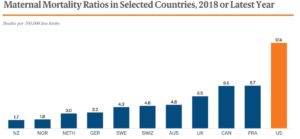

Even though most are preventable, maternal deaths[2] in the country have been increasing since 2000. This is so much so, that the U.S. has a maternal mortality ratio (MMR) more than double that of other high-income countries, with 17 maternal deaths for every 100,000 live births (Figure 1, below).

This also stands in stark contrast to a promising global trend, whereby evidence suggests that the global MMR is in decline – by 38% between 2000 and 2017, from 342 deaths to 211 deaths per 100,000 live births. Shockingly, the U.S. is one of only 2 countries (alongside the Dominican Republic) to report a significant increase in its MMR since 2000.

Figure 1. Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) in the U.S. compared to other high-income countries.

Policy Recommendation: Developing AI to Reduce Maternal Mortality.

There has been an increased budgetary focus on maternal mortality in recent months, with The White House fiscal 2022 budget requesting $200 million to expand maternal care – with a specific focus on the disparity in death rate between black mothers and white mothers. This renewed focus and monetary supply needs to be put to good use.

Evidence shows that Artificial Intelligence (AI)-based interventions have the potential to drastically reduce the number of maternal deaths in the U.S. The following evidence-based policy recommendations therefore have the potential to advance SDG 3 and Target 3.1:

Proposal 1: Using AI Prediction Models

A recent paper summarised the available evidence on AI-based algorithms (such as Machine Learning, or ‘ML’, a sub-type of AI), and found that there are promising methods available for the development of methods (prediction models) to better diagnose, identify and monitor women during pregnancy, labour and postpartum[3].

The researchers found that ML methods and existing data have been successfully used in research settings to predict preterm birth rate (PTB; when a baby is born too early, usually before 37 weeks of pregnancy have been completed), preeclampsia, mortality, hypertensive disorders during pregnancy, labour, and delivery and postpartum depression.

Proposal 2: Better Monitoring using AI Tools

AI technology can also help to curb maternal mortality rates through increased monitoring of mothers’ activity postpartum (after birth). This is already being trialled in low-resource settings such as Africa, but could also be applied to low-income areas of the U.S. For example, it has been reported that in a first-of-its-kind study, AI-enabled devices have been supplied by a New York-based company to 1,000 women in Uganda in order to identify at-risk cases using data such as respiratory rate, oxygen levels, pulse, temperature and blood pressure.

There is also increased commercial appetite to work towards the common goal of reducing maternal mortality – with Google having very recently announced a partnership with Northwestern Memorial Hospital to use AI to make ultrasounds more accessible, in a bid to cut the MMR by half.

Potential Setbacks

The most substantial roadblock of note is that researchers have recognised that AI for perinatal health is in its nascent stages. As such, time, effort and resources will be required in order to initially develop the requisite AI tools, before going on to trial them in clinical populations.

Conclusions

In summary, Proposal 1 & 2 (ideally run in parallel) are for the U.S., on a national level, to invest in the development of AI technologies (e.g., app-based ML algorithms, for use in clinical practice) for (1) the better prediction, and (2) increased monitoring of key indicators which are known to lead to maternal mortality. Leveraging the power of AI-based tools has the potential to advance towards the UN’s SDG 3 – and specifically Target 3.1 – whilst addressing the U.S. increasing rates of maternal mortality.

– O’Dell, Bessie – Sustainable Development Policy Fellow

Uncover impact opportunities in pursuit of the 17 SDGs, progress of ongoing AI + ML initiatives, and open resources & datasets for you to get involved here.

Learn more about the Goal 3: Good Health & Wellbeing.

References

Collier, A. Y., & Molina, R. L. (2019). Maternal Mortality in the United States: Updates on Trends, Causes, and Solutions. NeoReviews, 20(10), e561–e574.

Oprescu, AM, Miró-amarante, G, García-Díaz, L, et al. Artificial intelligence in pregnancy: a scoping review. IEEE Access 2020; 8: 181450–181484.

Ramakrishnan, R., Rao, S., & He, J. R. (2021). Perinatal health predictors using artificial intelligence: A review. Women’s Health, 17, 17455065211046132.

Reader, R. (2022). Google wants to use AI to cut the maternal mortality rate by half. Available at: https://www.fastcompany.com/90734110/google-wants-to-use-ai-to-cut-the-maternal-mortality-rate-by-half [accessed 11 May 2022].

The Commonwealth Fund (2020). Maternal Mortality and Maternity Care in the United States Compared to 10 Other Developed Countries. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications [accessed 12 May 2022].

The White House (2022). President’s FY 2022 Budget Advances Equity Across Government. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov [accessed 12 May 2022].

Thompson Reuters (2020). Ugandan medics deploy AI to stop women dying after childbirth. Available at: https://news.trust.org/item/20200131160316-lp5sv/ [accessed 12 May 2022].

UNICEF (n.d.). Maternal Mortality. Available at: https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/maternal-mortality/ [accessed 11 May 2022].

World Health Organisation (2019). Maternal mortality. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality [accessed 11 May 2022].

[1] Specifically, the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) is defined as the number of maternal deaths during a given time period per 100,000 live births during the same time period.

[2] The Commonwealth Fund (2020) and the World Health Organisation (WHO) (2019) defines maternal death as ‘death while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes. Used by the World Health Organization (WHO) in international comparisons, this measure is reported as a ratio per 100,000 births.’

[3] Note that this is a literature review rather than a systematic review, and so (as noted by the authors) it is ‘ it is subject to biases such as publication bias and reviewer bias regarding choice of studies included and biases due to non-assessment of quality of studies included’.