By: Lindsey Asis, Senior Project Manager, AI for Good Foundation

Yesterday, November 1, 2021, was World Vegan Day. I would like to preface this blog post with the fact that I was myself vegan for 4 years, and recently transitioned to a vegetarian diet that largely excludes dairy. Regardless of my personal experience, I believe there is much to learn and discuss relating to veganism, specifically its implications on the environment, food justice, and ethics regarding animal rights. With COP26 occurring the same week as World Vegan Day, we are provided with an opportunity to think about how global food systems affect progress towards #SDG13, Climate Action, and our roles within these systems. I argue that veganism should not be a shiny, unreachable ideal of following food rules precisely, but rather a practice of critically examining your relationship with food and how it impacts the larger world.

Why Vegan?

For decades and with increasing popularity, plant-based diets have been advocated for due to their health benefits, low environmental impact, and ethical considerations. Veganism is considered to be one of the healthiest lifestyles as those who follow it have a 32% lower risk than their meat-eating counterparts for cardiovascular disease and reduced risks for type 2 diabetes, colon, prostate, and breast cancers, and decreased symptoms of arthritis.

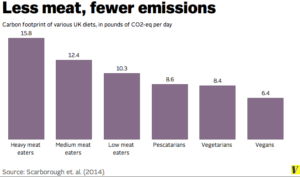

While these benefits are certainly rewarding, I became vegan due to its reduced impact on the environment. Plant-based diets have the lowest carbon footprint of any diet; a vegan carbon footprint is approximately 6.4 pounds of carbon dioxide per day, while heavy meat diets weigh-in 15.8 pounds per day. This is understandable considering that growing vegetables is a much more efficient use of land and water resources than meat, which requires years of resources to grow and be killed for consumption. The IPCC supports vegan diets as “a major opportunity for mitigating and adapting to climate change” and recommends the reduction of meat consumption in its policy recommendation.

A large sect of vegans choose the lifestyle due to ethics, specifically, animal rights. The basic tenant of this philosophy is the rejection of speciesism, or the “practice of treating members of one species as morally more important than members of other species.” Popularized in the 1970s by Peter Singer, speciesism contends that humans are superior to animals, allowing for their consumption, and that some animals are more morally protected than others. While meat-eaters may not find themselves to be speciesist, animal rights activists and ethicists believe that this captures the moral view of animals in meat-eating populations. Animal rights-centered vegans believe all life to be valued equally, and for it to be unethical to kill or exploit members of other species.

Finally, many cultures practice a completely or largely plant-based diet, rooted in hundreds of contexts and histories. Ital is the food practice of Rastafarians, a Jamaican movement developed in the 1930s. Ital, stemming from the word “vital,” holds that all food should be natural, free of preservatives, and meat. Ethiopian and Eritrean traditional foods are almost all completely plant-based, largely because of the fasting tradition of Orthodox Christians that abstain from animal products for 200 days of the year. Finally, India has the largest population of vegetarians in the world: 400 million people. While all of India is not meat-free, vegetarianism is highly popular largely because major religions in India- Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism- all practice the tenet of nonviolence towards all living things, Ahimsa. While veganism is becoming increasingly popular in western societies, it is important to remember that the practice has been integral to millions of people for centuries.

Deconstructing the White, Privileged Vegan

Many people critique veganism as being expensive, and largely only accepted and normal within white, wealthy communities. This criticism is not without base, especially in western society. Many mainstream vegan and animal rights organizations “normalize the white, thin, heterosexual body as the model of health and the normative image of vegans.” This is harmful on a multitude of levels; not only does it erase and co-opt the identities of those practicing veganism into a monolith of whiteness, but it intrinsically values thinness as a model of health that is the ideal to obtain. As we fight to dismantle oppression in society, especially fatphobia and racism, our critical lens must also extend to the subtle, parasitic values being portrayed alongside seemingly neutral topics like veganism.

People of color have actively sought to deconstruct the image of white veganism in favor of a more holistic, intersectional understanding of plant-based lifestyles. One school of thought is that veganism can be considered decolonizing in nature, as it rejects the practice of dairy farming that was integral to settler colonialism in North America. Many indigenous people to North America are “lactose intolerant” because they are not able to digest the dairy that they were exposed to post-colonization, furthering a concept that the inability to adapt to western influence is abnormal. Moreover, the ethics of veganism is in line with key tenants to Indigenous legal orders in Canada, namely that of a disavowal of human exceptionalism, a value of species interrelation, and sustainability. In the United States, Black Americans are three times more likely to be vegan than the general population, largely due to historical factors and the desire to create resilience and health within Black communities. Disproportionately affected by obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and hypertension due to systemic racism, veganism functions to “unlearn destructive habits that have been taught by families and centuries of oppression.” Plant-based diets are a means of resiliency and empowerment, and not just fixated upon an ideal of beauty. In short, veganism does not solely belong to skinny white people; it is a powerful and meaningful lifestyle undertaken for thousands of reasons, in thousands of contexts.

Another critique is that veganism is only an option for those who are wealthy and have access to fresh, nutritious foods. This criticism is indeed quite accurate, or at least the access component. However, that does not mean we should cast veganism aside as unattainable; rather, we should work to ensure food justice for all, regardless of them being vegan or not. As argued in “Questioning the Concept of Vegan Privilege: A Commentary,” veganism itself is not the privilege, but rather the ability to make choices about the food you consume. Critical Animal Studies (CAS) recognizes that “veganism may not be affordable or achievable due to income or geographic location”, and that people do not have equal access to healthy food. When considering or prescribing veganism as a climate solution, it is necessary to consider the mitigating and preventative factors that face disadvantaged populations.

Finally, critics of vegans make the case that it is not the “cruelty-free” lifestyle it claims to be. While strict vegans place no harm on animals in restricting all animal by-products from their lives, many vegans do not consider the environmental and social harms of the foods that they continue eating, such as industrial agriculture or unethical labor practices. As a previous vegan and now vegetarian, I am still grappling with and learning to mitigate this reality. CAS states that vegans must also “be concerned about the exploitation of workers who make the foods they eat, the clothes they wear, and the technology they use.” Across the world, disadvantaged populations such as migrant workers are placed in slave-like positions, including child labor. To label veganism as cruelty-free is to absolve those who are privileged from the horrors that are upholding their consumption.

The Answer? (Hint: There’s Not One Answer)

In the age of climate change, all of us who are concerned with the state of the world cannot help but look internally to see how they can help our collective future. For many, including myself, this means being conscious about the foods that we eat and the impacts that they have. I have the privilege to decide what I eat and found that it was a lifestyle choice that I was comfortable making. However, I am under no illusion that the rest of the world can or should follow suit. More importantly, I have grown more aware that universal veganism is not a perfect solution for climate change.

One element that I feel often gets lost in discourse revolving around veganism is that it does not have to be all or nothing. To demonize those who are not able to fully commit, especially those who do not have the means, is both elitist and unproductive. Rather, we should remind those that small changes can have a world of impact. For example, the difference between a heavy meat eater and a light meat eater in terms of carbon emissions is greater than that between vegetarians and vegans, meaning that simply eating less meat can have a significant impact. Additionally, our prescription of plant-based lifestyles should be culturally sensitive and competent. Some places do not have the choice to stop eating meat, and the impetus for change should fall greater on those who consume the most meat, namely western nations. Overall, there is no one-size-fits-all for mitigating meat consumption for climate change. We have to be intentional in our language, and aware of the colonial histories that inform our current environmental predicament.

Finally, regardless of one’s dietary habits, we must critically examine our food systems across the board. To be vegan does not make one immediately ethical; there is a world of injustice not only happening to animals, but millions of humans and our environment. From pesticide use, to emissions in transporting fruits across the world, to human rights abuses and trafficking, current veganism is inherently not cruelty-free. There are so many webs of impact that are inextricable, cutting across SDGs of No Hunger, Good Health and Wellbeing, Decent Work and Economic Growth, Sustainable Production and Consumption, Life on Water and Land, and obviously Climate Action (2, 3, 8, 12, 13, 14, 15, respectively). In re-envisioning our diets to fight climate change, we must pull back the curtain on all the harm we place on our world. At the AI for Good Foundation, we are doing our part by raising awareness and access to research through our upcoming Climate Trend Scanner and Open Data Catalogue projects. For now:

- Lower your consumption of meat, especially red meat, as much as possible

- Support local farms and farmworkers, and eat seasonal fruits and vegetables

- Research and examine the supply chain as much as possible of the things you consume

- Buy organic and fair trade whenever possible

- Follow vegans of color on social media for recipe ideas