Issue 4, Wednesday, August 1, 2018

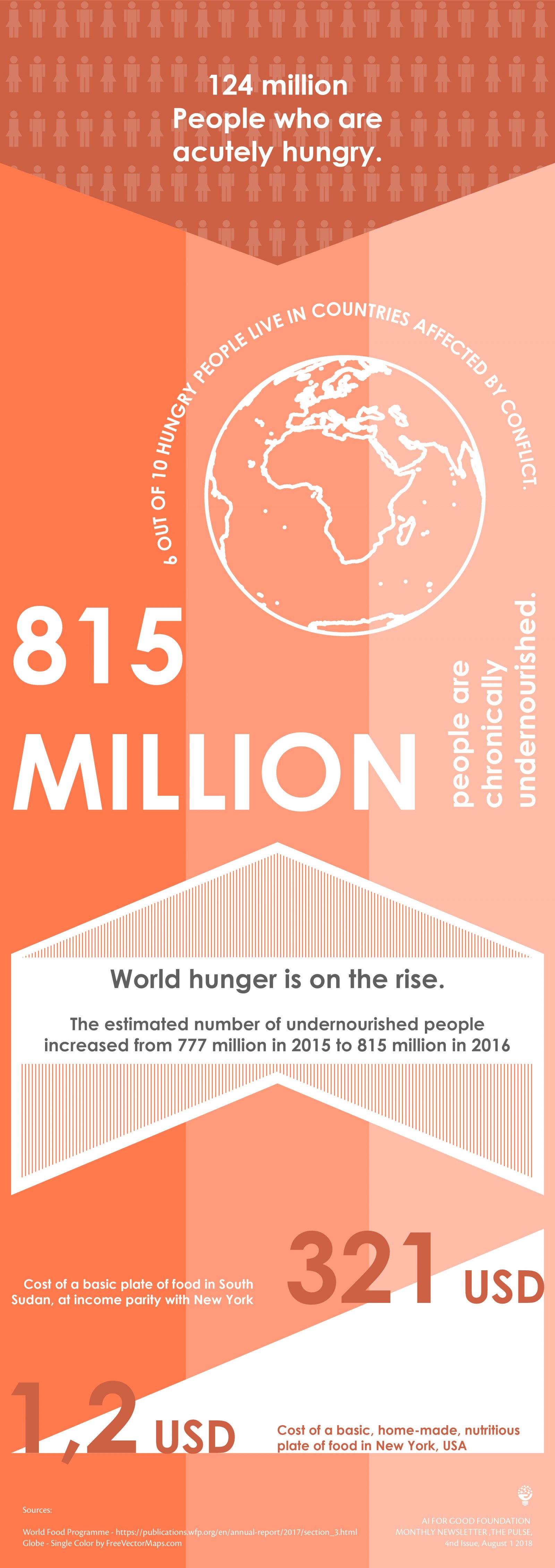

Dear Reader, One quarter of the world’s working population is engaged in agriculture. Most of these people still lack basic farming automation techniques as well as the knowledge necessary to optimize what they grow and how. Over the next decade we will add about 1.2 billion people to the world’s population, mostly in countries at risk of systemic crop failures. Not only does this represent an enormous problem for food security in the developing world, but also global social repercussions. In the coming years, we can expect increased social tensions, migratory pressures, and potentially lost generations without employment and appropriate skills training. The bad news is that we are likely far behind where we would need to be in order to keep up with these trends. The good news is that there are many things that we can do to make the best of a bad situation, and perhaps even mitigate some aspects. With large coordinated efforts, anything is possible.

- Helping farmers to make better decisions;

- Bringing basic farming automation to small hold farmers;

- Supporting healthy supply chains and market regulation;

- Improving farming technology to develop resilient and high-yielding varieties;

- Incentivising entrepreneurial activity across the sector, at the grass roots level.

Monthly Interview on Sustainable Agriculture: David Hughes

Could you tell us a little bit about your background and interest in the use of data analytics in agriculture, and the future of sustainable agriculture more broadly?

I am Irish, and the country of Ireland is one for which global hunger is a pressing issue deserving of more attention given the importance the Irish famine has played in our nation’s history. For me as I contrast Ireland of 1848 with Sub Saharan Africa of 2018 I see too many similarities. Smallholder farmers, predominantly women, pulling diseased crops from the ground the absence of knowledge that could help them grow more food. The world in 2018 is one being massively transformed by changes in technology. Of course, pointedly, increases in AI. In many developed countries, AI represents an existential threat to their labor force. Our contention that PlantVillage is that AI represents an enormous opportunity in developing world countries because it could provide put in the phone an expert who could help smallholder, farmers, grow more food. Our work with experts at the International Institute for Tropical Agriculture in Tanzania established that Nuru, our AI assistant was much better than local extension workers whose job it is to help farmers. But of course the advantage is that the AI assistant can be deployed much more broadly as every village has a smartphone.So, AI and Nuru have the potential to be deployed across hundreds of millions of phones providing farmers the type of high level of expertise one previously only had from human to human encounters. It would be a great tragedy if we have this massively enabling technology like AI driven smartphones and in 10 years times have not pulled the hundreds of millions of small holder farmers out of subsistence farming. AI cannot just be about getting millenials a meal, lift home or a date! Or for rich companies to become richer through the commodification via the advertisement model.

What do you think are the biggest challenges that lie ahead?

We have found that the ability to train a machine to diagnose crop diseases depends on the close interaction with public funded scientists who are experts in those diseases. At least in our system, there is no AI without human intelligence. The challenge then is ensuring that those -public funded scientists see the value in the AI tool we are creating and work with us to create it. We are not building a tool to replace them but to amplify their expertise and spread it across the globe to regions they either cannot reach or only rarely get to.

How do you think that technology, and Artificial Intelligence, in particular, might facilitate solutions to these challenges?

We at PlantVillage think it is entirely possible to have an AI-assisted network of hundreds of millions of phones helping farmers diagnose problems and the international community to be continually updated on new threats that might affect food security. We believe that this is all a public good. We are fully committed to supporting the mission of governments in low income countries understand what threats are affecting their farmers and deliver the timely advice that is needed. We built our AI assistant to be as good as experts but also to work offline which is critical where no connections exist. And to allow public institutions to send the most relevant information on best practices. For Africa we do this in French, Swahili, Twi and English.

What are the key organizations that will enable achieving these goals?

We released our AI assistant, Nuru three weeks ago with the UN FAO and CGIAR (notably IITA). https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=plantvillage.nuru. These are the two prominent public bodies focused on food security globally. I will spend a year at UN FAO in Rome from next week which is a testament to how important I think these institutes are.

What are some notable projects or specific steps that are being taken today to enable universal access to food around the world?

The fundamental constraint is a lack of knowledge. Knowledge of what the problem is and knowledge of what the solution is. In the context of global climate change and on ongoing globalization, we can fully expect smallholder farmers around the world will be subject to more and more threats to their food supply. So, the knowledge delivery system has to be very dynamic and adaptive.

If you are interested in our news or events, please sign up to our Newsletter.

»Find out more about our projects